Kazakh oil exports across Russia interrupted for fourth time this year

Kazakhstan is dependent on Russia for its main oil export route, which has run into repeated problems since Nur-Sultan refused to support Moscow’s war.

An oil pipeline across southern Russia that carries the bulk of Kazakh crude exports has again limited shipments, threatening one of Kazakhstan’s most-important sources of hard currency and further fueling speculation that Moscow is deliberately punishing Nur-Sultan for not supporting its war on Ukraine.

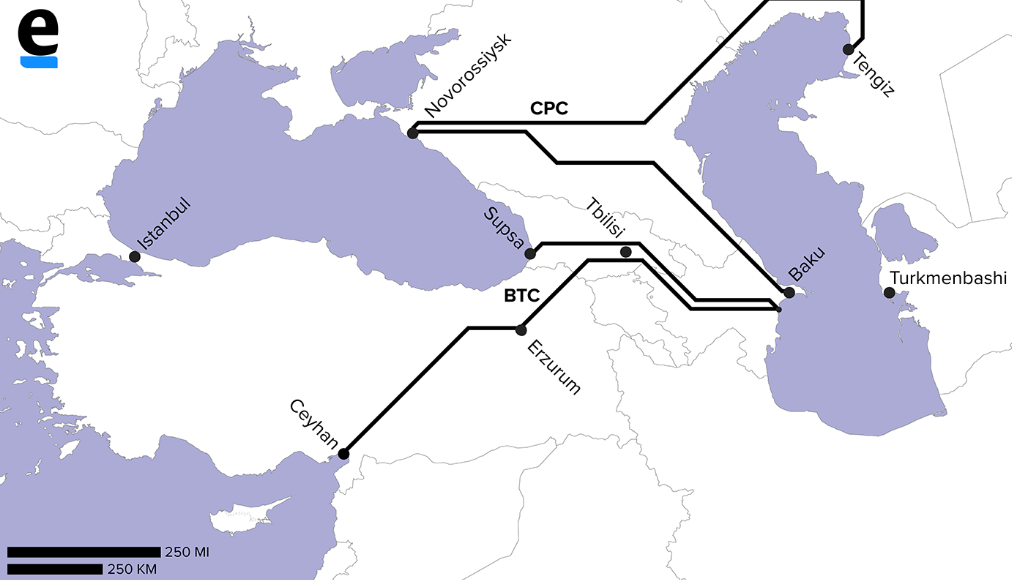

The Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), which runs the pipeline from western Kazakhstan to Novorossiysk on Russia’s Black Sea coast, says it had detected damage to underwater equipment, forcing it to take two of three tanker loading berths out of service.

“During routine maintenance work by diving teams […] cracks were found in the nodes fixing the submarine sleeves to the buoyancy tanks,” the Russia-led consortium reported on August 22. The CPC says it believes the Novorossiysk terminal was damaged because of “exceptionally difficult weather conditions” last winter.

It is the fourth time this year that operations at the CPC, which handles about 1 percent of global crude and is the single largest source of Kazakh government tax revenues, have been interrupted.

The first suspension occurred in March, when the consortium said damage to two loading moorings had been caused by a storm. Independent observers expressed skepticism about this explanation, especially since the consortium’s Western partners were unable to conduct their own investigation. Loadings resumed after a month.

Then, in June, CPC deliveries were again interrupted following what Russian officials said was the discovery of World War II-era anti-ship ordnance in the area.

The following month, a Russian court ordered the pipeline to halt work due to environmental violations. A few days later a higher court allowed shipments to resume and slapped the consortium with a nominal fine.

Analysts saw a Kremlin warning in that brief shutdown because it came shortly after Kazakhstan President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev told Vladimir Putin at a public forum that he would not recognize Russian-backed satellite states on Ukrainian territory and a day after he offered to make Kazakh energy resources available to Europe to help mitigate the impact of the Ukraine war.

This time, the CPC consortium has made more of an effort to explain the cause of the trouble. Its statement was accompanied by underwater photos of cracked equipment and an infographic showing the entire loading system with a detailed description of how it works. It provided no clarification on how long repairs will take. Reuters reported on August 23 that repairs could be at least a month and that, in the meantime, the single remaining berth would work in “intensive mode” and continue to transfer 60-70 percent of the total capacity.

In 2021, the CPC shipped 60.7 million tons of oil, equivalent to roughly 510 million barrels, through the Novorossiysk terminal. Of that total, 53 million tons came from the Kashagan, Tengiz and Karachaganak fields in western Kazakhstan. Another 7.7 million tons was delivered by Russian companies.

Last year oil revenues accounted for about 44 percent of Kazakhstan’s budget, meaning this one pipeline contributes about a third of government revenues.

The news of the shutdown did not cause as much of a stir in Kazakhstan this time, with some appearing resigned to the on-off troubles amid the widespread belief that Russia is deliberately punishing the country for its independent position on the war.

“In my opinion, the work of the CPC in 2022 is like litmus paper,” wrote Askar Aisautov, an Almaty civil engineer specializing in the construction of pipelines, on Facebook. Based on whether the pipeline is working, “you can judge the magnitude of tension in relations between the Kremlin and Akorda.”

Yet, writing on Telegram, Nurlan Zhumagulov, head of the Union of Oil Service Companies of Kazakhstan, a lobby group, offered an alternative explanation for the pipeline’s troubles: the corrosive effects of corruption.

A year ago, he pointed out, the small investigative newspaper Nasha Versiya reported that in March 2021, CPC replaced its former contractor, Rotterdam-based Smit Lamnalco, which had been servicing the marine terminal for 12 years, with a local company, Transneft-Service, after an opaque tender. Nasha Versiya reported that the new contractor, despite minimal experience, was charging 30 times more for its services and argued that it was funneling the proceeds offshore. That August, a spill at the terminal dumped at least 70 tons of oil into the Black Sea, CPC confirmed; WWF Russia said the spill was no less than 100 tons.

Blaming “lawlessness at the CPC,” Zhumagulov assessed “geopolitics and the storm” as less likely culprits for the work stoppages than “corruption and the irresponsibility of the Russian contractor.”

Either way, that is bad news for Kazakhstan, which has few other outlets for its oil.

During the earlier shutdowns, Kazakh authorities explored alternative routes, such as taking oil across the Caspian Sea and then delivering it to Europe through the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline, but this solution proved costly. Critics of the government have raised questions about why Kazakhstan failed to diversify oil export routes in good time so as to avoid excess dependence on a single Russian-controlled pipeline.